The promise of the internet has always been in two main areas: knowledge aggregation (content) and interpersonal connectivity (community). Everything comes from these two factors, combined with the computational power of the computer. This is especially true in inherently human endeavors like education. With the internet as a tool, teachers, who have historically been isolated from each other and who spend more time with children during the day than with peers, ought to have greater capacity to collaborate around problems of practice. And further, with the right platform, teacher sharing of research, practices and solutions ought to lead to a knowledge base that still to this day does not exist as it does in other industries.

The 2000s proved that connectivity and knowledge aggregation can work at scale. Social network platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn showed how connectivity can build community online. And user-generated content management systems like Wikipedia and GitHub demonstrated the extraordinary capability of knowledge sharing. These organizations and others have realized the two key promises of the internet for the general user and for certain professions.

But in education, we have yet to fully realize this promise. Teachers remain largely isolated in their classrooms, and the absence of a professional memory — a knowledge base that collects, shares and organizes knowledge in an intuitive way — is an ongoing crime.

It is not for want of trying. Efforts to build content repositories are many, but the mantra of “if you build it, they will come” has proven over and over again to be untrue, and the web continues to host scores of teaching material archives that are collecting digital dust. Social network platforms, however, have recently proven more successful, and Facebook and Twitter have developed resilient communities around areas of interest. These networks have been powerful and responsive resources for some teachers, but they still lack the ability to aggregate knowledge in a way that moves the profession as a whole.

What follows is a survey of the landscape. Examples of current efforts and challenges are enumerated below. Broadly organized into content-centric and community-centric resources, the following examples show ways in which the internet is beginning to yield network effects for educators.

CONTENT: KNOWLEDGE AGGREGATION

Content repositories came first to education, and most discussed here have been around for a decade or longer. They have each, to varying degrees, achieved some kind of success, but collectively they have yet to solve to problem of the systemic absence of professional memory. Here is a representative sample:

- TeachersPayTeachers (TPT): Founded in 2006 and the largest and most well known of the content repositories, TPT is a simple and effective marketplace for lessons. Vendors (often but not exclusively teachers) post teaching materials that teachers can purchase. Money from the sale goes to the vendor and a percentage goes to the platform. TPT has famously minted millionaire teachers who have sold seven figures worth of materials. Further, the CEO has said “2/3 of teachers in the US are active members of our platform” (EdWeek, 2018) As a result of its success, TPT has spawned a host of copycats, including entries by TES Global and Amazon, most of which have faded from competition.

- Key Lesson: TPT validates that teachers are hungry for support in developing and improving their lessons. So hungry, in fact, that many are willing to pay for materials.

- Key Strength: The business model — and therefore the sustainability model — is clear and successful.

- Key Weakness: In addition to being uneven in its quality, the knowledge stored on TPT is closed, locked in documents protected by proprietary licensing. A professional knowledge base for education will never be developed from knowledge trapped in documents, each of which requires its own fee. TPT has created a successful business, and it aids some teachers, but it does not solve the essential knowledge problem for the sector.

- BetterLesson: Spun out in 2009 as a sector-wide version of TFANet, Teach for America’s internal network, BetterLesson began as a crowdsourced lesson sharing platform, it evolved into a grant-driven, master teacher lesson distribution channel, and it pivoted to a professional development service that offers coaching from expert teachers. A B Corporation, BetterLesson has tread the line between purpose and profit.

- Key Lesson: BetterLesson’s pivots show that sustainable, scalable business models are hard to come by in the world of free curriculum sharing.

- Key Strength: A curated selection of carefully vetted, highly structured, consistently formatted content promises that materials will be high quality.

- Key Weakness: In its current iteration as a professional development service, BetterLesson aims neither to be a universal content source nor a community platform. Once, the mission was to provide a better lesson, now it is to make your lessons better. This isn’t a weakness, it’s simply aimed now at a different target.

- OER Commons: A property of the Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management in Education (ISKME), OER Commons is the purest platform in regards to providing open education resources (OER) to teachers. Launched in 2007, OER Commons is built around principles of openness, and its sustainability model seems to be built on funding from ISKME and professional development services that teach teachers how to use its platform and content. Content on OER Commons is drawn from open sites around the web and created by users.

- Key Lesson: Alignment with the OER movement and OER-focused organizations has enabled sustainable funding and successful partnerships that have buoyed OER Commons over the years.

- Key Strength: OER Commons demonstrates all the functionality OER advocates ask for, which, in theory, should make for a powerful tool.

- Key Weakness: The design of OER Commons is particularly clunky. It is likely that most users arrive but rarely return.

- ShareMyLesson: Launched in 2012, ShareMyLesson was the AFT’s response to teacher sharing platforms. It quickly attracted a large amount of content and users, but is now an exemplar of the teacher resource collection box. It looks different than it did at its founding, but it functions much the same now as then. Borrowing from the traditional search paradigm, ShareMyLesson offers numerous filters for key word results to search queries, like Amazon.

- Key Lesson: ShareMyLesson is the standard case study for why traditional searches of archives of documents don’t work for educators.

- Key Strength: The backing of a large teacher union drives sustainable funding and delivers some ongoing traffic. Like others above, it serves a dedicated corner of the sector, but will not solve the problem at scale.

- Key Weakness: With content both locked in documents and as diffuse and unorganized as it is, ShareMyLesson doesn’t have the digital architecture to aggregate its knowledge in scalable ways.

These four examples are representative players in a populated landscape of teacher resource platforms. They reflect: the sound business model, the mission-driven business, the business-minded mission, and the benevolent organization’s side project. Each has captured the attention (and for some: revenue) of different stakeholders: teachers, some districts and schools, funders and states, and union members. Notably, their goals are — or once were — to provide content for teachers, and while none has scaled fully in a way that solves the collective problem, they have each demonstrated facets of what an integrated solution might look like.

COMMUNITY: CONNECTIVITY

As the fervor for content platforms waned, enthusiasm for social networks waxed. The late 2010s saw major foundations pivot to supporting “Networks for School Improvement” (Gates), “Networked Improvement Communities” (Carnegie), and other socially-oriented approaches. The momentum for this kind of work has been growing organically on social networks for more than a decade now. Below are three examples:

- EdModo: Edmodo succeeded early at creating communities of teachers. Founded in 2008, Edmodo sought to integrate a learning management system with resource sharing and social networking, all in one. Its original business model was to attract a large number of users to its free utilities and then monetize the traffic, at least in part through selling apps embedded in the platform. One notable feature of Edmodo is the topics feature, which enabled teachers to form and join groups around topics, and then post discussions to a shared newsfeed. The English Language Arts group grew to over half a million teachers and teachers could expect numerous responses to questions posed to the group.

- Key Lesson: At its founding, the leading thinking was that building a large community first was the path towards later success. This did not play out.

- Key Strength: Critical masses of teachers, gathered by discipline or interest, provide a ready-access resource for other teachers. At its peak, an English teacher could expect 20 responses to a question within a few hours.

- Key Weakness: It’s unclear if Edmodo was ever profitable, or even sustainable. In August of 2022, Edmodo permanently shut down.

- Twitter: Over time, education-focused hashtags have emerged on Twitter, such as #edchat, #dtk12chat, #pblchat, and many others, and teachers have formed communities that participate in regularly scheduled conversations. The format follows typical Twitter structures, and users feel connected to colleagues who often link to other online spaces with usable knowledge. It’s not uncommon to hear people say that they go to Twitter for community and TeachersPayTeachers for content.

- Key Lesson: Teachers crave community, and Twitter provides a way for teachers to connect across school and district boundaries. Many teachers describe Twitter as a place to gather ideas and feel connected.

- Key Strength: With a ready-built community, Twitter enables teachers to find their tribe and participate in community experiences both during scheduled chats and on their own schedules.

- Key Weakness: Ephemerality. Twitter has few means for storing or organizing content. Once an item has disappeared down a feed, while it can be searched for, it is effectively gone, living only in the waning memory of those who read it when it appeared.

- Facebook: Like Twitter, Facebook provides a ready-made community: the people are already there. Over time, teachers have used the groups function in Facebook to form groups of professional interest, and on group pages, they can post questions and links, and offer answers and support to other teachers. These groups, which typically require approval from an administrator to join, have become sites of vigorous conversation similar to what is described above for Edmodo.

- Key Lesson: Again, teachers crave community. Facebook groups (and also communities like Twitter, Edmodo, and TeachersPayTeachers) have shown an ability to attract large numbers, which reflects significant demand.

- Key Strength: Numbers. As with Twitter, teachers are already on the platform, and it has only taken time for teachers to organize.

- Key Weakness: Also as with Twitter, while conversations can draw significant participation, there is no meaningful way to store and organize content.

WHAT DO TEACHERS ACTUALLY USE?

“Teachers need to curate the knowledge in their class. They need control over the curriculum. Teachers need to be trusted with the risky business of learning. It is what we trained for. We love it. We can do it.”

“Miss Smith” (2018)

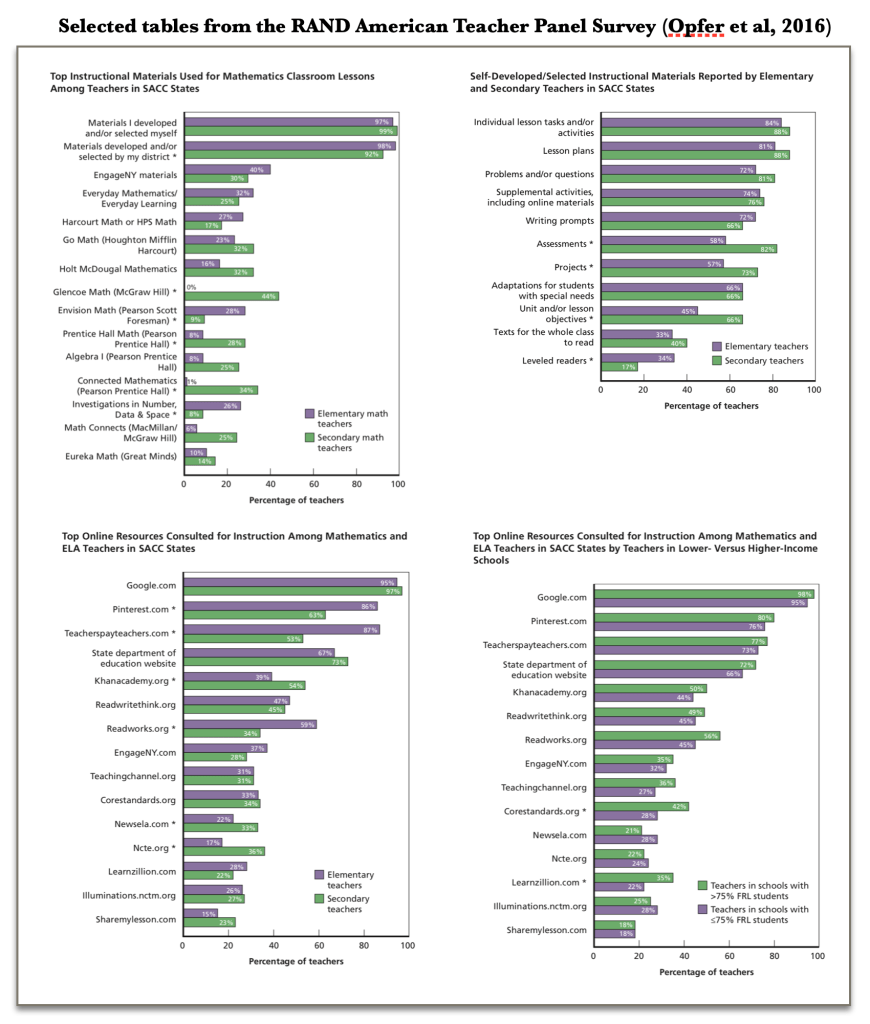

For all this, where do teachers actually go when they seek ideas, curriculum, or advice? RAND Corporation’s 2015 American Teacher Panel survey (Opfer et al., 2016) gathered self-reports from a representative sample of teachers nationwide on where they go online for resources, breaking down responses by elementary and secondary teachers, by ELA and math teachers, and by teachers in high- and low-SES schools. What follows are particularly salient conclusions, with select tables on the next page:

Virtually every teacher uses materials they develop or select themselves. 98% of respondents — elementary and high school, ELA and math — say they use materials that they develop or select on their own, reminding stakeholders that the teacher is the ultimate arbiter of what happens in the classroom. This does not mean that teachers don’t use resources or tools provided to them (94-95% of teachers report using materials developed or selected by their district), but it indicates that virtually every teacher supplements or supplants provided or required materials with materials that they deem appropriate. This significant conclusion affirms the importance of providing powerful tools for teachers to search, find, create, and customize teaching materials online.

When teachers develop or select materials on their own, they develop granular curricular objects, scaled from lesson plans down to individual assessments, prompts, activities, or other lesson tasks. Teachers are looking sometimes to replace lessons in their curriculum, and other times to tweak an assessment here, an activity there, a discussion question to start off a unit, etc. Notably, the second most significant factor in teacher use of instructional materials is the “availability of materials,” following only the reasonable first factor, which is “District curriculum framework, map, or guidelines.” Teacher attention to granular materials and the apparent limited availability of these materials argues that readily available, high quality, granular materials would provide value to teachers, who ultimately (appropriately) participate in crafting the learning experience for students.

Virtually all teachers go online to search for materials. And virtually all of them go to Google. Across elementary and secondary teachers, math and ELA teachers, low-SES and high-SES schools, an average of 96-97% of teachers report going to Google for instructional materials.

Pinterest and Teachers Pay Teachers are the most visited sites, after Google. Across low and high SES environments, 78% and 75% of teachers report visiting Pinterest and TPT for instructional resources. When broken down by elementary and secondary levels, however, secondary teachers do report visiting the state department of education website more than Pinterest and TPT, but 63% and 53% of secondary teachers still report visiting these sites for materials.

Problematically, the quality of content on the most heavily used sites is consistently low. Or inconsistent at best. According one study’s measure, from a sample of over 1,200 mathematics materials found on Pinterest, 75% of the tasks required only lower order thinking, as defined by the lower two levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Hu et al, 2018).

The present state is pretty grim. Coherent, high quality curriculum is available (often for free), but it is diffuse. Instead of visiting these resources, teachers seeking to supplement and customize their classrooms most frequently visit sites where the content costs them money, scores low on measures of quality, and/or is trapped in closed formats.

How did we get here? What follows in the next section are descriptions of the persistent challenges that have plagued efforts to make curriculum accessible to teachers online.

The (Unrealized) Promise of the Internet

Fulfilling the Need: Program Design

Appendix A — Mission: Improvement

Leave a comment